Cold-chain deployment: Questions from history

On 28th and 29th October 2025, we are hosting a two-day international conference at University of Birmingham to advance the collaborative thinking on how, as a community, we can provide holistic, sustainable, affordable, and resilient cooling and cold-chain services to all; how we can embed this approach quickly enough to avoid locking-in cooling emissions for years or decades; and of course identify the research, trade, and commercial opportunities this offers to the UK. Dr Ed Hammond, who is working with the Clean Cooling Network on our design of equitable and sustainable Community Cooling Solutions for Africa, looks at some questions from history.

In countries that have well-established, comprehensive, fully integrated cold-chains, such as the UK and the United States, the technical development of this infrastructure generally appears to have been driven by either one of two motives: food security, or economics. However, regardless of the original driver, their deployment has bought about changes in diets, culture, health, and lifestyle, as well as environmental harm, energy consumption and wealth generation.

Responding to the food security driver through cold storage began at a “household” level with ice. Stores based on the use of this simple technology can be traced back nearly 4000 years and a surprise to many readers will be that similar designs were in use in the UK until the 1950s, in one form or another.

What is an Ice House?

An “Ice House” is a building for storing ice throughout the year. Traditionally built partly or completely underground, they were often located near a natural source of ice in winter, such as a river or freshwater lake. During the cold season, ice and snow would be taken into the ice house where it was insulated against melting with straw or sawdust. Through this simple approach, it would stay frozen for many months, providing cooling during the warmer months of the year, and in some cases even until the following winter.

The Modern Integrated Cold-chain

In more recent history, economic drivers have been the dominant motivation for investment in cold-chains, underpinned by a desire to get a better price for produce through transporting it to more distant and lucrative markets, or to delay sale until market prices were favourable.

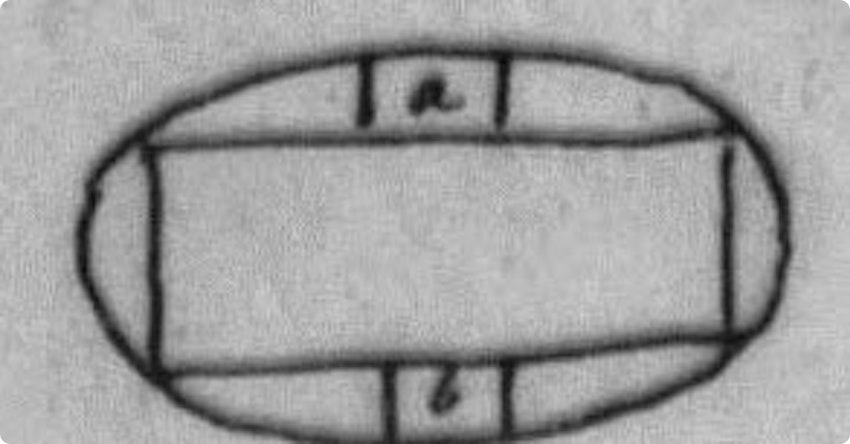

What may be considered as the start of the modern integrated cold-chain (rather than simply a static food preservation facility, or cold store) also began with naturally occurring ice. In 1803 Thomas Moore patented his “refrigerator” invention, which was simply constructed by placing a tin box inside an oval cedar tub and filling the gaps between box and tub with ice. The whole unit was then covered with a hinged lid and insulated on the outside with rabbit fur and coarse woollen cloth. Moore developed the box in the USA to transport butter from Georgetown to his home in Montgomery County, Maryland. He claimed that just four or five trips would pay back the capital investment in the system, because the butter would fetch such a premium at his local market due to its excellent condition.

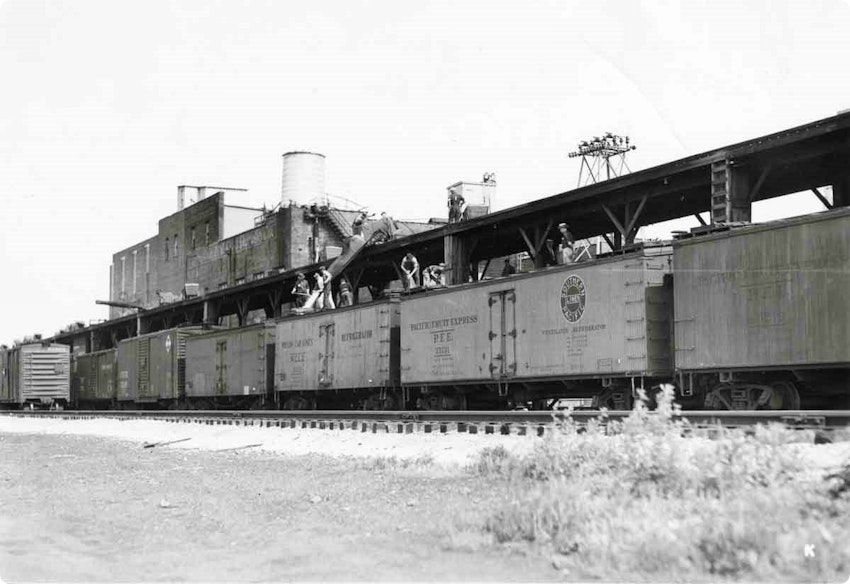

Over the next century, mobile refrigerators just increased in size, with trains (rail cars) and ships packed with ice to carry fruits and meat. In the case of the latter, the introduction of this cold-chain technology meant that cattle no longer had to be transported long distances prior to slaughter and the associated economic model for livestock farming evolved, with new processing local to farms and expansion of holdings to supply increasing volumes for more distant, and lucrative, export markets. Farmers were no longer constrained to sell only to the local population and, in turn, the growth of owns was no longer constrained by the surrounding belt of farms that had previously been essential to a supply of fresh food.

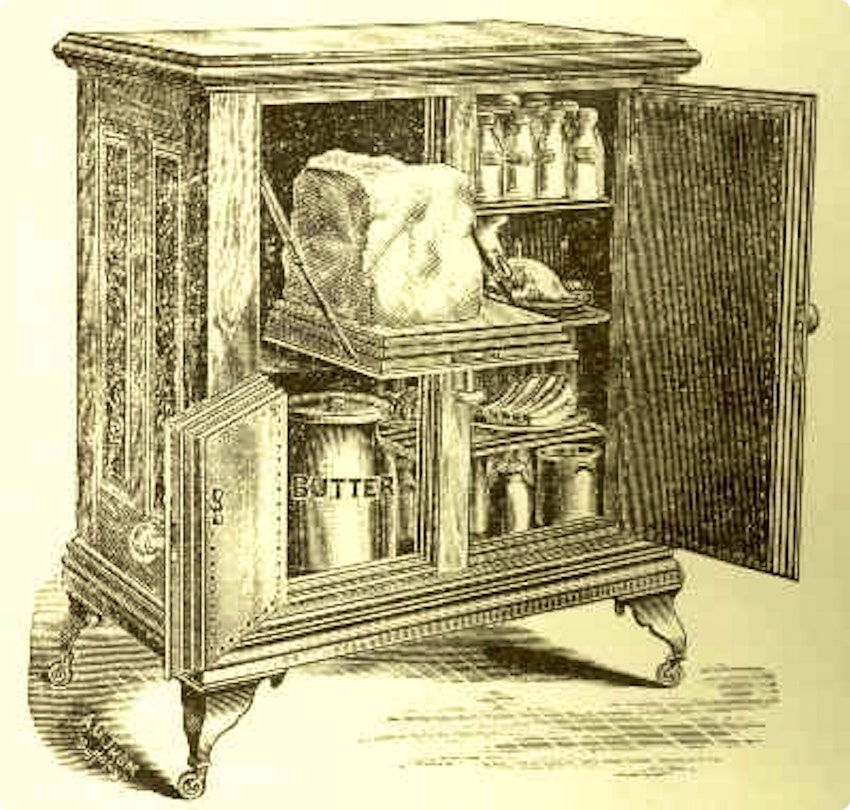

With the availability of chilled (preserved) produce, markets, retailers and homes began to invest in ice fridges and the integrated cold-chain was completed from field to fork.

In the early years of cold-chain expansion, refrigerators continued to be largely based on the use of ice and although the technology was developing rapidly during the first half of the 20th century, the equipment for mechanical cooling was large, inefficient and expensive. It also usually required a mechanic or operating engineer to be on-hand at all times. This limited its use to large warehouses and ice making factories, with most of the smaller or mobile applications being cooled by ice alone (indeed, ice cooled reefers were still in use in the early 1970s).

However, technological innovation and economic opportunities saw widespread introduction of mechanical cooling units by the 1950s. By this point the cold-chain was universally accepted as a means to deliver fresher, quality produce to consumers and increase revenues and profits. It followed that produce could be grown overseas, easily imported, and enjoying “out of season” food became normalised in the developed countries of the world.

New Technology & Environmental Impact

As cold-chain deployment grew at pace in advanced economies, new technology was developed and added to the mix. These included large static ice making plants to supplement the natural ice harvests, large chilled warehouses, small mechanical refrigerators for homes, and engine driven units for transport vehicles such as lorries, trucks and vans. With mechanical cooling also came the ability to freeze some produce and realise even longer storage periods. However, alongside these beneficial innovations, through their widespread adoption came the unforeseen problem of a growing carbon footprint.

History has seen an evolution through many types of refrigerants, from solid ice to modern liquid chemicals, as well as incremental improvements in refrigeration equipment. Some of these have been driven by safety concerns, some by energy efficiency and environmental impact, and many for cost reduction. Most recently, it is the increased awareness of environmental impact that is driving change. Natural refrigerants and low GWP (Global Warming Potential) refrigerants are now the preferred option, along with life-cycle operational costs or TEWI (Total Equivalent Warming Impact) where energy consumption is also considered.

Changes in other sectors, such as the electrification of transport, is also making a mark. As battery powered vehicles struggle to deliver sufficient energy to onboard refrigeration systems for maintaining a useful cooling range, thermal storage is being investigated. And history is repeating itself, albeit with many lessons learned, as “ice” becomes a means of delivering mobile cooling once again. This time, however, incorporating improvements in energy supply and considerations for renewable power, improved reliability of equipment, and natural refrigerants. Whether using Ice directly or Eutectic Packs as the thermal storage technology, refrigerated transport vehicles can be overall lighter, and have a significantly reduced Carbon Footprint than if fitted with mechanical cooling driven by an engine or battery power.

With this model in mind, if ice is available, food producers and farmers only need insulated boxes for produce storage. And ice can be made year-round at a factory near a market to enable a cold-chain, without the need for expensive assets at every link in the chain.

The Cold-chain and the Global South

Although food security and seasonal storage was an early driver for the cold-chain, it appears to have been economics that dominated the most significant deployment in the mature developed nations of the world. Firstly, to improve the quality of produce upon arrival at the market, increasing its value, then to access new, more distant yet more lucrative markets. Its widespread adoption led to further benefits, with significant wealth generation, growth of towns and business and export trade.

In relating this to the Global South, the obvious question is why have neither of these drivers led to the widespread deployment of cold-chains in Africa? Undoubtedly, the cold-chain could reduce food waste, could reduce hunger, and could generate wealth across the continent in much the same way it has in the Global North. What is it that is needed to stimulate a cold-chain in the Global South?

Looking first at the food security motivation. There is clearly hunger and malnutrition in Africa that could be avoided, which implies food security is not currently being achieved. Cold-chain technology exists but is not used. In the past people went to great lengths to cut and store ice to store food. And yet now that convenient, tried and tested cooling technology exists, it is not used. Are we missing something in our analysis of the problem? Are there barriers we do not yet understand?

The example of the ice house was typical of the wealthier households or communities who always had the economic power to buy commodities such as food. The need for cold storage was a result of an annual scarcity of food through the winter. Food security was an issue for everyone, every year, rich or poor. Perhaps Africa is not affected in the same way, with no long winter seasons between harvests and significant areas growing year-round? Perhaps the scarcity is less predictable?

Turning to economics, reducing food waste and feeding the hungriest (also poorest) markets was never likely to be enabled through a financially driven expansion. There is little incentive for investment where there is no wealth or where the cost of cooling is likely to outstrip the economic value of the food. However, export markets do exist and the exploitation of these (assuming fair trading terms) could enable wealth creation in poorer communities, potentially improving their ability to produce more food and underpinning the financial means to afford it. In this way, the cold-chain can be an enabling technology to reduce waste and feed today’s poorest people, if it, along with fair-trading terms, are shared with them.

As the cold-chain became established in the developed world, the supply of exotic and out of season produce became normalised, however, perhaps these are eating habits of the wealthy rather than the hungry? Either way, these demands have led to high value exports from regions such as Africa.

Or perhaps the real motivation was the accidental enablers; the side effects of the cold-chain? The cold-chain enabled the expansion of towns and cities as food could travel from more distant sources. The result being a total dependency of urban areas, and many developed countries, on the cold-chain to import produce for their “food security”. Is it the unsustainable growth of populations, particularly in urban areas, that leads to the need for cooling? Europe’s average population density is 1.5 times higher than Africa’s; Europe is 75% urbanised, whilst Africa is only 44%. Perhaps population growth was the unseen driver of the cold-chain? Africa’s population already has significant regional variation, but with it projected to double overall by 2050, perhaps what history really teaches us is that dependency on cooling is coming to Africa, and now would be a good time to accelerate the deployment of a sustainable cold-chain!